Does Democracy have a Stupidity Problem?

Between the Financial Crisis, Brexit, Trump, and now Boris Johnson winning a ‘thumping’ majority, it has not been a good decade for democracy in the eyes of some people. Caroline Flint has alleged that Emily Thornberry blamed the Johnson’s triumph on the ‘stupidity’ of voters. Thornberry denies this and has begun legal action against Flint, but behind closed doors many people may think that democracy has a problem: it gives too much power to the stupid, ignorant, and misinformed. They just don’t have the stomach to publicly challenge the foundational belief that democracy is the cornerstone of a well-ordered state.

Emily Thornberry denies blaming Johnson’s election on the stupidity of voters.

Not everyone is so timid; epistocrats like Jason Brennan advocate a form of government in which those with political knowledge are granted more influence than those without. He is not in bad company, epistocrats draw on a tradition that includes Plato and John Stuart Mill. Brennan’s argument can be crudely summarised as follows: democracy is unacceptable because it allows the ignorant and uninformed to use political power to harm innocent people. Individuals are allowed to make bad choices so long as it only harms themselves, as soon as it hurts innocent bystanders their actions become immoral; the state should be bound by similar rules. Take the recent British election as an example, the public have elected a government whose campaign relied on pandering to prejudice, misinformation, outright lies, and the evasion of scrutiny. The government will pursue a legislative agenda that will almost certainly make the country poorer and more isolated. To many people this result is the consequence of the metropolitan London elite ignoring the voice of the provincial working class and not capitulating to Brexit. Vox Populi, Vox Dei and if you ignore the voice of God there will be consequences. However, for the epistocrat, the question is why should we listen to people who are ignorant or misinformed? Why should their opinion be respected or even solicited in the first place? If you are ill, you go to a doctor; if you have car trouble, you go to a garage; if you want to build a house, you commission an architect. So why should we listen to people who do not understand the complexities of politics and international trade?

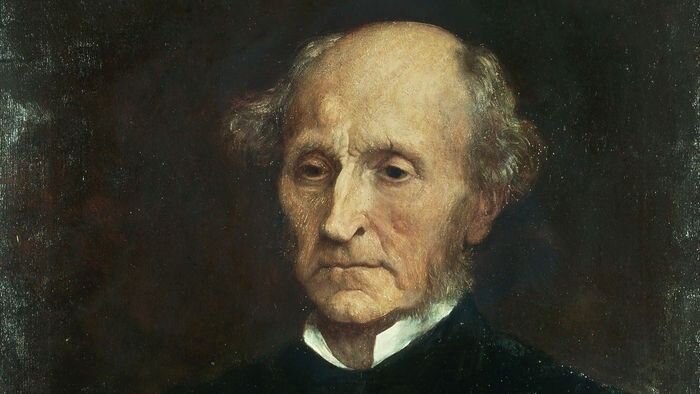

J.S. Mill, the intellectual forerunner of many current epistocrats.

The short answer is that determining who counts as knowledgeable is not as straight forward as it seems. If you are like me, you think that those who wield power ought to be accountable in some fashion. That unconstrained and unchecked power is anathema to liberty. My concern with epistocracy is that those who ‘set the test’ will do so in a way that is unconstrained and uninvigilated. This is dangerous. Literacy tests, for example, were used to disenfranchise black citizens in the USA during Jim Crow. However, the basic problem is not with the abuse of power, it is that even if it were used wisely, it would still be open to abuse. Vulnerability is sufficient to make epistocracy unjust. It would leave people in the same position as a slave, under the arbitrary power of their owner. It does not matter if the slave-owner is good or evil, it is the possession of unconstrained power that is repellent. So too is it with epistocracy.

Democracy needs retrenchment, not disestablishment. Epistocracy throws the democratic baby out with the bath water. The problem with contemporary democracy is not that it allows the ignorant to vote, but that it does not furnish the civic education and social security that enables people to responsibly exercise their franchise. Democracy is not the be all and end all of a well-ordered state; there are numerous auxiliary institutions, political and social, necessary for democracy to function. Epistocrats may be correct that democracy unconstrained is dangerous, but, at least for republicans, it was never meant to be unconstrained. No power ever should be, and this brings us back to Boris Johnson.

The most worrying thing about the 2019 General Election is not Brexit, but the nebulous promise of constitutional reform. Buried on page 48 of the Conservative Manifesto is the promise that “after Brexit we also need to look at the broader aspects of our constitution: the relationship between the government, parliament and the courts.” It is plain that this is directed at entrenching the powers of the executive beyond the scrutiny of parliament and the courts. Johnson is going punish the institutions that were holding him back prior to the election. He seems poised to eviscerate the institutions of the state and rely solely on the authority of voters who are regularly inundated with misinformation, inadequately educated, and subject to constant insecurity. It is within his powers to do this. The British constitution is informal and held together by a gentlemen’s agreement to adhere to the customs and conventions. We may be about to find out what happens when the Prime Minister is not a gentleman and makes no pretext to be one. It will turn Britain into a test case for epistocratic scepticism.

If you are interested in the tension between democracy and epistocracy you can read my new article The Case for Epistocratic Republicanism either at Politics or here.